BAHRAMCHA, HELMAND PROVINCE

MIMLA, NANGARHAR PROVINCE

December 2021 / January 2022

Afghanistan is since years the biggest source of the world’s supply of illicit opium and heroin and has recently also become a major methamphetamine producer. While the new Taliban government in general vows to curb narcotics production and trafficking in Afghanistan, visits of the Swiss Institute for Global Affairs (SIGA) to a notorious narcotics bazaar that has seen a downturn in activity and to newly established heroin ‘laboratories’ elsewhere in the country paint a more complex picture.

A Talib in a compound in Bahramcha, Helmand Province, Afghanistan, that has, according to the Taliban, been a narcotics production facility that they have forcibly shut down (Franz J. Marty, 24th of December 2021)

Narcotics in Afghanistan & the Taliban’s Official Position

Since decades, Afghanistan is infamous for its fields of poppy flowers whose pods are scratched and later skimmed to harvest opium. The opium goo, at first white or pink, turns brown when it

oxidises and has an analgesic effect when smoked or taken in otherwise. Transported to crude processing facilities that Afghans simply call ‘korkhonaho’ (‘work houses’ or ‘factories’ in Dari, one

of Afghanistan’s official languages) and foreigners rather misleadingly ‘laboratories’ the raw opium is refined to morphine and then heroin base. Then it leaves the country raw or processed,

reaching drug users in neigbouring states, as well as the Middle East, Europe, Africa, and parts of North America.

A man in an opium poppy field in Mazor Dara, Nurgal District, Kunar Province, Afghanistan (Franz J. Marty, 2nd of May 2017)

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) estimated that, in 2020, approximately 85 % of the world’s supply of illicit opium and heroin originated from poppy fields at the feet of the Hindu Kush. And Afghanistan has made up similar high shares for many years. While figures on narcotics in Afghanistan by the United Nations are flawed and should be taken with more than a grain of salt, there is no doubt that Afghanistan is the biggest source of illicit opium and heroin worldwide.

Since a few years, Afghanistan has also seen a boom in the production of methamphetamines, after locals found out that one key ingredient, ephedrine, can be extracted from a bush that grows wild and in abundance in Afghanistan’s mountains.

In view of this and given that the prevention of narcotics production and trafficking is — apart from migration and counter-terrorism — one of the main points of interest in Afghanistan for the international community, the Taliban are under increased scrutiny with respect to their policies on narcotics. However, and as with many other issues, the Taliban have, even almost six months after they toppled the former western-backed Afghan Republic and returned to power in Afghanistan, so far not stated a clear policy on narcotics.

Officially, the Taliban, only days after they marched into the Afghan capital Kabul in mid-August 2021, vowed to ban narcotics. Later, the Taliban also announced to have fully staffed the counter-narcotics police, established a special court for narcotics related cases, and advertised seizures of narcotics.

In reality, the Taliban position on narcotics is far from clear though. For example, in an interview with the BBC, Taliban spokesman Bilal Karimi admitted that the Taliban «can’t take this [income from narcotics production] away from people without offering them something else». Moreover, exclusive field work from SIGA in two places in Afghanistan — Bahramcha, a narcotics trafficking bazaar in the southern province of Helmand; and Mimla, an area in the eastern province of Nangarhar — shows how different, and sometimes questionable, the Taliban’s handling of the narcotics issue looks on the ground.

Bahramcha — A Narcotics Trafficking Hotspot Being Shut Down…

Bahramcha is notorious. Said to be one of the most important places for trafficking narcotics out of Afghanistan, anyone who has looked into narcotics in Afghanistan has heard of Bahramcha. But few outsiders ever visited. Reasons for the latter are Bahramcha’s remote location at the disputed Afghan-Pakistani border separated from the rest of Afghanistan by the vast desert covering southern Helmand as well as its reputation as a lawless smugglers’ place.

When SIGA nevertheless managed to go to Bahramcha, it was not as expected. Arriving in late December 2021, the many lights glowing in the darkness of a winter evening indicated a much bigger settlement than one would assume. The next morning, it became clear that most of the lights belonged to traditional residential compounds that are enclosed by high mud walls, hiding from sight what goes on inside them. The bazaar, the only public space, is small, just two, three dusty streets with simple store fronts. Some sell clothes or everyday items; in front of one stood colourful bicycles for children; many others are repair shops for cars that usually arrive battered from the long travel through the desert; yet others provide satellite-based WiFi, the only means of telecommunication, as there is no mobile telephone network available in Bahramcha. Numerous places were also closed, dilapidated metal shutters hiding what, if anything, the rooms behind them hold. Whether open or closed, over many buildings in the bazaar the white banners of the Taliban fluttered beside satellite dishes in the light breeze.

Despite many open shops and the fact that it is the only trading place for miles, Bahramcha’s bazaar was, in late December 2021, anything but a hub of activity. During the one and a half days that the Taliban allowed the SIGA fellow to stay, there were only a very few people and cars in the bazaar and even less in the labyrinth of alleyways in the residential areas. «Business completely crashed», one shopkeeper in Bahramcha told SIGA, with another agreeing. «During the past months, I haven’t even made enough money to pay the rent», the man added.

While the shopkeepers could or would not indicate the reasons for the economic downturn, apart from the effects of the general economic crisis following the Taliban takeover that hit every place across Afghanistan, it might well be due to what was lacking: there was no sign of opium or heroin, the commodities that are reported to have, so far, fuelled Bahramcha. While the absence of visible indications for narcotics trade might be expected in a western imagination of an underground black market, reality in Afghanistan is different. Journalists have, after the Taliban takeover, documented the open display and trade of opium in other bazaars in southern Afghanistan (for an example from Kandahar, see here); which made the complete absence of it in Bahramcha surprising.

«We have outlawed opium and heroin here», Abdullah Omari, the Taliban governor of Bahramcha, which the Taliban have elevated to a separate district, told SIGA. «We did not issue a written edict but told this to the people and coordinated with local notables», Abdullah Omari, whose jet-black turban matches the colour of his long beard, explained when asked for further details. «Most followed the order and closed the ‘korkhonaho’; we shut down the few that didn’t», Abdullah Omari added, sitting on a raffia mat on the concrete veranda of a rundown compound at the edge of the bazaar that serves as his office and accommodation.

A group of men who used to be involved in the trafficking of narcotics in Bahramcha confirmed this to SIGA, complaining that they are now out of business. «The Taliban are serious about their prohibition of the production and trafficking of drugs [in Bahramcha]», one of the smugglers assured SIGA, «they don’t just say it for appearances».

Eventually and after much hesitation, the local Taliban showed SIGA two of the allegedly forcefully shut down narcotics production facilities in Bahramcha. From the outside, the only thing separating them from the numerous other mud compounds were large Xs and warning marks — «خطر بند» («Danger. Closed») — sprayed in red over their gates and walls. Inside, they were practically empty. «We removed all the narcotics and equipment», the Talib accompanying SIGA claimed. In one compound, blue plastic barrels that were buried in the ground in a corner and were, according to the Talib, a secret stash for opium, were the only sign of previous illegal activities. In the other, a plastic bag and a small round tub sported brown residue, apparently from opium paste, but apart from that the compound did not hold any sign of narcotics production.

The gate to a compound in Bahramcha, Helmand Province, Afghanistan, that the Taliban claimed was a narcotics production facility that they had forcefully shut down and marked with an X and «خطر بند» («Danger. Closed») (Franz J. Marty, 24th of December 2021)

The empty courtyard of a compound in Bahramcha, Helmand Province, Afghanistan, that the Taliban claimed was a narcotics production facility that they had forcefully shut down (Franz J. Marty, 24th of December 2021)

… or Still Running?

While all this suggested an actual clampdown on narcotics in Bahramcha, digging further, it became clear that the situation is not as straightforward as displayed by the Taliban. «The compounds [that the Taliban claimed to have shut down] lack the tell-tale signs for heroin production», David Mansfield, who is, since over 20 years, in detail researching narcotics in Afghanistan, told SIGA after reviewing photos that the SIGA fellow had taken during his visit. «Heroin production leaves a lot of chemical residues and other rubbish which is hard to clean up», Mansfield elaborated further, «but these places don’t show any of this».

Furthermore, later three smugglers told SIGA in private conversations that, although the Taliban had acted against narcotics in Bahramcha, they did not shut down everything. Two of the men estimated that between 40% and 60% of the heroin ‘laboratories’ are still working in Bahramcha. «This happens without the consent of the Taliban, and they would close these places down if they would find them», one of the smugglers asserted. The other disagreed: «the Taliban know about the still open ‘korkhonaho’, but it is not clear whether or what they will be doing about this». The latter is more credible, as it is unlikely that numerous ‘laboratories’ could continue operating without the Taliban noticing or looking the other way.

Two other smugglers based outside of Bahramcha also confirmed that narcotics trafficking is still continuing via Bahramcha. «About a month ago, I sold 95 kilogrammes of ‘shisha’ [local name for crystal meth] in Bahramcha», one smuggler told SIGA in late December 2021 in Lashkar Goh, the capital of Helmand. And on 12th of January 2022, an interlocutor relayed to SIGA that another smuggler had a consignment of narcotics en route to Bahramcha, assuring that the trafficking continues without major problems or changes.

In this context, it has to be noted that the trafficking of narcotics over the disputed Afghan-Pakistani border in Bahramcha has, independently of who rules Afghanistan, become more difficult. As the SIGA fellow saw himself, Pakistan has completed the border fence — a double fence topped by barbed wire with a narrow space in between — in Bahramcha and the only way across the border are two semi-official border gates. As several sources, including smugglers, confirmed to SIGA, there is no, or at least no significant smuggling through the border gates, which are only allowed to be crossed by people who possess a Pakistani ID or Pakistani refugee card, which many Afghans living in border areas have, but not for cargo. This, however, does not mean that there is no smuggling via Bahramcha anymore; just that smugglers are now forced to take a wide detour through the desert west of Bahramcha, where there is, at least to date, no border fence.

A Talib in front of the Pakistani border fence in Bahramcha, Helmand Province, Afghanistan (Franz J. Marty, 23rd of December 2021)

In view of all the above, the Taliban seem to have acted to some extent against narcotics in Bahramcha, but not in a comprehensive manner. Why this has been the case could, as the Taliban in Bahramcha were adamant that they have outlawed all narcotics production and trafficking, not be determined.

One possible and likely reason is that the Taliban in Bahramcha realise that completely shutting down the narcotics production and trafficking would probably mean the end of Bahramcha, as the desolate place surrounded by bleak small mountains at the edge of the desert does not offer any other livelihood. Another alleged explanation that was put forward by several sources was that the Taliban make their actions against narcotics contingent on the official recognition of their government by the international community. While this is conceivable, the sources that purported this were seemingly speculating and not basing this on factual evidence or tangible indications.

Whatever the reason is, the situation in Bahramcha shows that the Taliban lack a consistent policy when it comes to narcotics.

Mimla — Sprouting of Heroin ‘Laboratories’

That the Taliban apparently have no clear line on narcotics is also apparent elsewhere in the country, for example in Mimla, an area of Khogyani District in the eastern Afghan province of Nangarhar.

On 12th of January 2022, the SIGA fellow visited two ‘korkhona’ refining opium to morphine and heroin base in Mimla, both of which were, according to the men who run them, only recently established. «Before the Taliban overthrew the Afghan Republic [in August 2021], the ‘arbaki’ [by now defunct Afghan Local Police] were not allowing ‘korkhonaho’ and also enforced this», one of the men told SIGA. «So far, the Taliban have said nothing, and we can freely work», he added. The man from the other ‘laboratory’ also explained that their business has, now under the Taliban, become easier, as they are not anymore targeted by raids as had been the case under the previous government.

A facility in Mimla, Khogyani District, Nangarhar Province, Afghanistan, where opium is refined to morphine base, from which heroin can be produced. As other such facilities, it is rather simple consisting of an array of barrels, a press, a few plastic tubs, and clothes for filtering. (Franz J. Marty, 12th of January 2022)

To what extent this led to an expansion of the narcotics business is disputed. The man in charge of the larger ‘korkhona’ asserted that the numbers of heroin production facilities has multiplied, from perviously 5 or 6 to now around 40 in the greater Khogyani area, which includes the districts of Khogyani, Sherzad, and Pachir Aw Agam. The man responsible for the smaller ‘laboratory’ claimed though that the number of facilities has not changed, just that they moved to lower, more easily reachable areas. However, as another local recounted that many of his personal friends recently started working in heroin ‘laboratories’, the former appears more likely.

What can be said for sure is that the existence of heroin production facilities only a few minutes’ drive away from Mimla bazaar, a locally important market place, is new. This was confirmed by locals as well as David Mansfield, who has worked in these areas over many years and stated that, so far, heroin ‘laboratories’ used to be located in remote mountain areas in Sherzad District and not as far down as the places visited by SIGA.

Ochre-coloured morphine base at the bottom of a barrel with opium brew in a crude narcotics production facility in Mimla, Khogyani District, Nangarhar Province, Afghanistan (Franz J. Marty, 12th of January 2022)

Morphine base is filtered out by pouring opium brew through a cloth wrapped around a sieve in a simple narcotics production facility in Mimla, Khogyani District, Nangarhar Province, Afghanistan (Franz J. Marty, 12th of January 2022)

While this all indicates a more permissive environment for narcotics in Mimla under the Taliban, it does not answer the question whether or to what extent the Taliban are involved. «So far, the Taliban have neither allowed nor prohibited heroin production», the man in charge of the larger heroin ‘laboratory’ in Mimla said. The man responsible for the smaller facility confirmed this, but added that he expects the Taliban to ban narcotics completely once they have properly established their government. That the Taliban are aware of the heroin production in Mimla is no question, as it is an open secret. In the smaller ‘laboratory’ there was even an armed Talib present; what exactly he was doing there was unclear, but he certainly had no issue with the heroin production going on in front of him.

In this regard, it has to be noted that the often-purported notion that the Taliban control the narcotics business in Afghanistan or reap astronomic profits from it, is wrong, as detailed research of David Mansfield and his team shows. To the contrary, in a conversation with SIGA, Mansfield pointed out that, if the Taliban would effectively enforce narcotics ban, they would draw the ire of their rural constituencies, who partly base their livelihood on the narcotics business. And this, in turn, could threaten their rule.

That the Taliban indeed take the welfare of their rural constituencies, even if they are narcotics producers, into consideration was, independently of each other, corroborated by the two men running the two visited heroin ‘laboratories’. «Before the Taliban took over the government, they did tax the production and trafficking of heroin; since they are in power, they haven’t collected taxes from us anymore», one of the men said. This was later confirmed by the other, who added that the Taliban would have abated these taxes «due to the poverty of the people» in the ongoing economic crisis.

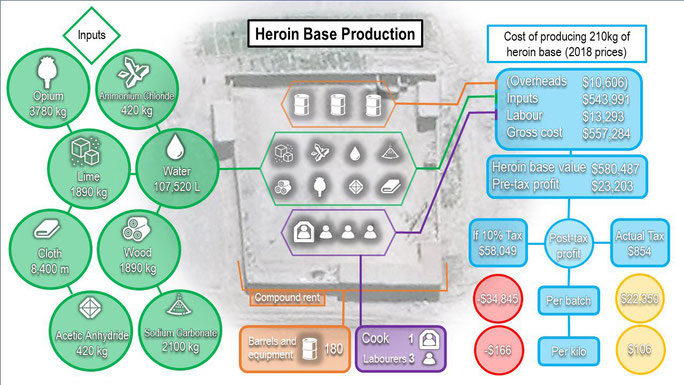

In this context, it is important to point out that the two men running heroin ‘laboratories’ in Mimla, just as most people involved in the narcotics production and trafficking in Afghanistan, might make a living out of narcotics, but are not getting rich. Wages of labourers and ‘ustodon’ (‘professors’ in Dari, meaning men who have the knowledge how to produce heroin base) are, although not bad for local standards, still modest. A narcotics smuggler in Bahramcha also complained to SIGA that the existing profits are split up between so many people in the long chain of narcotics trafficking that each individual does not earn that much. Moreover, Mansfield emphasised that many extrapolations of profits derived from narcotics in Afghanistan fail to take the significant costs of production into account, leading to distorted results. As such, and although there are some larger traders in the business that make good money, the notion of rich cartels or affluent drug lords controlling the narcotics market in Afghanistan are amiss.

Infographic of necessary inputs and costs for the production of heroin base in Afghanistan as of 2021 (courtesy of David Mansfield)

Conclusion

All the above suggests that the most likely explanation for the Taliban’s inconsistent actions against narcotics production and trafficking is that they try to walk a tightrope of conflicting interests. Such interests are considerations of what benefits a ban of narcotics could give them, namely better chances of international recognition and — from a Taliban perspective maybe even more important — being true to their religious conviction that deems narcotics haram, and the reality that the livelihood of so many Afghans is partly dependent on the narcotics business and that a ban would have potentially uncontrollable consequences. Another possibility is that the Taliban are, giving this difficult balance act, shirking to make a clear decision, leaving local commanders and officials to decide whether or how much to do against narcotics.

Both would explain the current situation where rules and attitudes seem to vary from place to place and Talib to Talib. That this can lead to more than odd situations was exemplified by an anecdote relayed to SIGA in the northern Afghan province of Kunduz in January 2022, where a man was jailed by the Taliban for possessing two kilogrammes of heroin but had troubles to grasp that he had committed a crime as he had a receipt with an official stamp, confirming that he had duly paid the Taliban taxes for his narcotics.

Whatever the reasons behind the Taliban’s current inconsistent behaviour towards narcotics are, the fact that a Taliban official, after having learned of SIGA’s visit to the ‘korkhonaho’ in Mimla, contacted a man from one ‘laboratory’, but only criticised him for showing a foreigner the heroin production, but not for producing narcotics in the first place, suggests that the Taliban are more concerned about appearances than whether or not narcotics are being produced.

Franz J. Marty

Kommentar schreiben