China’s leadership prioritizes efforts to control information and its flow into and within the country. Efforts are also undertaken to influence and guide how that information might be perceived and interpreted, both domestically and internationally. This is realized by controlling the news, establishing an extensive web of Internet controls and censorship, as well as specific monitoring and control of social media. In fact, controlling information is a core component of mobilizing public opinion. When it comes to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, various reports have indicated the divergence between China’s official neutral stance and the narrative elements found in Chinese state-controlled media. Over the past several months, a sort of alignment between Chinese and Russian state media messaging related to the war in Ukraine can be observed, allowing Kremlin narratives to help shaping Chinese public perception of the war.

The aim of this article is to offer a glimpse into the Chinese concept of public opinion warfare and how it is reflected in Chinese state media messaging about the war in Ukraine.

Public Opinion Warfare: Definitions

Central to the Chinese conception of political warfare (zhengzhi zhan 政治战) are the so-called “three warfares” (san zhan 三战) – public opinion warfare (yulun zhan 舆论战), psychological warfare (xinli zhan 心理战), and legal warfare (falü zhan 法律战). As an integrated and interrelated whole, they are intended to be conducted in combination. The “three warfares” seek to employ various types of information, for example, diplomatic, political, economic, and military. Moreover, they employ a range of national resources, including military, civilian, and hard and soft power, guided by the overall military strategy, to secure the political initiative and psychological advantage over an opponent, debilitating one’s opponent while strengthening one’s own will and influencing third parties.[1]

According to Chinese analysts, public opinion warfare, also termed “media warfare” or “consensus warfare”, targets audiences through information derived and propagated by mass information channels, including the Internet, television, radio, newspapers, movies, and other forms of media. It is seen as a powerful element of “informationized warfare” (xinxihua zhanzheng 信息化战争) as it can reach every part of society and has an especially wide impact. Chinese experts argue that the goal of public opinion warfare is “to shape public and decision-maker perceptions and opinions, shifting perceptions of the overall balance of strength between oneself and one’s opponent.”[2] Successful public opinion warfare is said to target three audiences: the domestic population, the adversary’s population and decision makers (both military and civilian), and neutral and third-party states and organizations. Regarded as both national and local responsibility, public opinion warfare is undertaken not only by the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), but also by the People’s Armed Police (PAP), national and local media, spokespeople, netizens, and other groups.[3] In this article, the focus will be on the presentation of public opinion warfare via Chinese state-controlled media messaging.

Pillars of Public Opinion Warfare

Chinese writings highlight certain themes that are central to the construct and framework of public opinion warfare. These themes include:

-

Follow top-down guidance

Public opinion warfare must support national political, diplomatic, and military objectives. Its actions must be consistent with the larger national strategy as laid out by the top levels of leadership. -

Emphasize preemption

Public opinion warfare is always under way. The side that plants its message first enjoys a significant advantage. In fact, Chinese analyses repeatedly emphasize that “the first to sound grabs people, the first to enter establishes dominance (xian sheng duoren, xianru weizhu 先声夺人,先入为主).” Essentially, the Chinese seek to define the terms of the debate and parameters of coverage.[4] -

Be flexible and adaptive

Public opinion warfare messaging must be implemented in a flexible manner, incorporating shifts in strategic, political, and military contexts. At the same time, different messages are tailored for different audiences instead of pursuing a one-size-fits-all approach. -

Exploit all channels of information dissemination

To ensure maximum effectiveness of public opinion, all available resources must be exploited, so that a given message is reiterated, reinforced by different sources and different versions. Chinese military writings regularly invoke the ideals of combining peacetime and wartime operations, civil-military integration, and military-local unity (pingzhan jiehe, junmin jiehe, jundi yiti 平战结合,军民结合,军地一体).[5]

The Official Role

China has not yet taken a clear position on the war in Ukraine. Officially, the Chinese government has neither condemned nor condoned the Russian attack and has refrained from calling it an “invasion”. Instead, Chinese authorities and party-state media outlets typically refer to it as the “Ukraine issue” (Wukelan wenti 乌克兰问题), “Ukraine situation” (Wukelan jushi 乌克兰局势), or “Ukraine crisis” (Wukelan weiji 乌克兰危机).

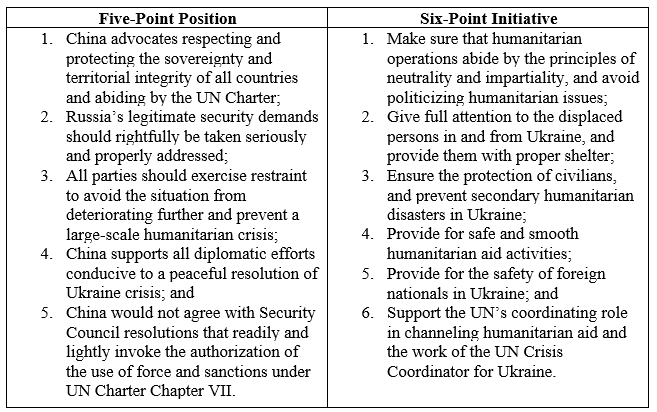

The official position on Ukraine is partially outlined in Xi Jinping’s “four musts” (si ge yinggai 四个应该): (1) the sovereignty and territorial integrity of all countries must be respected; (2) the purposes and principles of the UN Charter must be fully observed; (3) the legitimate security concerns of all countries must be taken seriously; and (4) all efforts that are conducive to the peaceful settlement of the crisis must be supported. In addition, China has put forward a five-point position (wu dian li chang 五点立场) and a six-point initiative (liu dian chang yi 六点倡议) on easing the humanitarian crisis.[6]

Source: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China.

According to a Xinhua news article, “China’s stance, widely recognized by Russia and Ukraine, among others, is in line with the fundamental and long-term interests of the world, and its concrete actions have injected much needed confidence and new impetus into the maintenance of global peace and stability.”[7] From the Chinese perspective, this unique position might allow it to play a pivotal role in facilitating peace talks and a short-term ceasefire between Russia and Ukraine.

State-Controlled Media: Echoes of Russia’s Language and Narratives

With regards to messaging about the war in Ukraine, it is apparent that Chinese state media (Global Times/Beijing Review/CGTN etc.) has been adopting Russian state media language and narratives over the past several months. Here are a few examples:

-

The portrayal of Ukraine and NATO as the aggressors and the idea that NATO expansion is to blame for the conflict has been pushed by Russian officials and state media. The anti-NATO expansion reasoning was picked up by several Chinese state-controlled channels. Below are two examples of such narratives, spread via the Twitter accounts of Global Times and Beijing Review.

Source: Twitter (screenshots).

-

The argument of “what about” is a consistent theme in Chinese state media messaging. Tweets from a diplomatic account in Japan (Consulate General of Russia in Niigata) and a Chinese state media account (ChinaQ&A) are presented below, essentially questioning why the activities of the USA and NATO in the former Yugoslavia, Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, and others, are not brought to the attention.

Source: Twitter (screenshots).

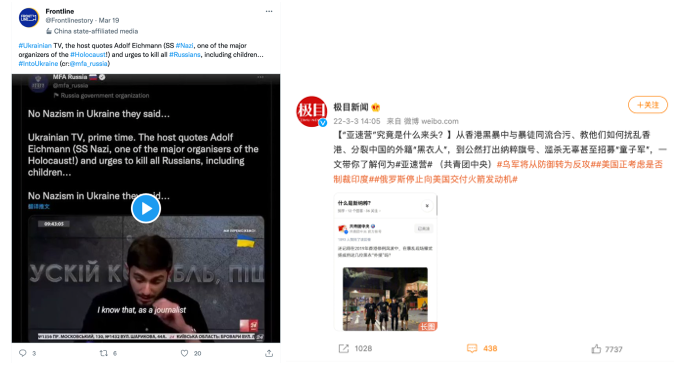

- Another example is the narrative adoption of “denazification” in Ukraine. The left screenshot shows the Chinese state-run media outlet Frontline retweeting Russian state media coverage of Ukrainian neo-Nazi groups. It is interesting to point out that on the Chinese microblogging platform Weibo, the term “Azov Battalion” seems more popular than “Nazis” and was given impetus by a March 3 post by the Communist Youth League (Gong qing tuan 共青团) account, introducing the group as a Nazi organization and linking it with the Anti-Extradition Bill Movement in Hong Kong (2019-2020) (right screenshot).

Source: Twitter and Weibo (screenshots).

-

Narrative alignment between Chinese and Russian messaging can also be observed in the specific language used to describe what is happening in Ukraine. As is the case within Russia to use terms like “special operation” or “special military operation” instead of “war” and “invasion”, we see Chinese officials and state media adopting the same language.

Source: Twitter (screenshots).

Influencing Public Opinion about the War

The echoing and dissemination of Russia’s preferred language and narratives in the Chinese information environment not only gives a boost to Kremlin disinformation, but also exemplifies the increasing alignment between narratives promoted by Chinese and Russian officials and entities. A recent article by The Washington Post has called China “Russia’s most powerful weapon for information warfare”, arguing that China’s state-controlled channels offer a powerful megaphone for shaping global understanding of the war in line with Kremlin rhetoric.[8] Seen in a broader context, this is related to the CCP’s efforts to maintain control over information which is required to influence society. Especially in the era of so-called informationization, the CCP strives to control various forms of news media.

The phenomenon of aligning state narratives in China’s media environment can help shaping the public perception and opinion of the war, even as the CCP government refrains from taking an official line.

Moreover, the topics of Ukraine, Nazism and foreign interference often became linked in Chinese online communities and discourse.

But how do Chinese citizens view the conflict in Ukraine? Can online opinions reflect the actual public opinion in China? As there are both supporting and alternative voices within China, it is difficult to gauge the public opinion on the war. For instance, an open letter signed by five renowned Chinese historians in denouncing the war was published on February 26, reading “as a country that was once also ravaged by war … we sympathize with the suffering of the Ukrainian people.”[9] Calling for an immediate end to the fighting, the letter warned the invasion could spark a “massive, global war.” Shortly later, over 130 alumni of China’s top universities issued a statement condemning the invasion which has been widely shared online.[10] Other forms of anti-war public opinion can be found in a variety of actions. But in general, such actions are very likely subject to censorship.

A recent survey conducted by the Carter Center China Focus may provide valuable insight into the Chinese public opinion on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The survey is conducted between March 28 and April 5, 2022, receiving a total of 4,886 responses from Chinese internet users. The results suggest that 75% of respondents agree that supporting Russia in the Russo-Ukrainian conflict is in China’s national interest, over 60% of respondents indicate that offering moral support to Russia is China’s best course of action, and that almost 60% of respondents support China mediating an end to the conflict.[11] Ultimately, the exposure to national state media and social media is believed to have contributed to a higher level of support for Russia.

The previous sections attempted to summarize the Chinese concept of public opinion warfare and to show how it is reflected in the state-controlled media narratives regarding the Ukraine war. Mass media being the main channel utilized to influence and guide Chinese public opinion includes but is not limited to state-controlled news media and social media. Other mass information channels such as television, radio, and movies etc., also play an important role in instilling certain public perceptions and opinions. In the case of the Russia-Ukraine war, it is difficult to figure out what the actual public opinion of the Chinese population is, and caution should be taken in assuming the levels of support for war, especially when the evidence comes from state media and state-linked social media. As it had been pointed out, Russian narratives are visibly seeded in the Chinese information environment. By citing each other as sources and expanding on each other’s angles, the ease with which Sino-Russian state media information cooperation can be selectively deployed becomes evident.

[1] Academy of Military Sciences Operations Theory and Regulations Research Department and Informationalized Operations Theory Research Office, Informationalized Operations Theory Study Guide (Beijing: AMS Press, November 2005), 403.

[2] Academy of Military Sciences Operations Theory and Regulations Research Department and Informationalized Operations Theory Research Office, Informationalized Operations Theory Study Guide, 405. And Liu Gaoping, Study Volume on Public Opinion Warfare (Beijing: NDU Press, 2005), 16-17.

[3] Dean Cheng, Cyber Dragon: Inside China’s Information Warfare and Cyber Operations (California, USA: Praeger, 2017), 51.

[4] Yao Fei, “Some Thoughts Regarding Our Military Anti-Secessionist Public Opinion and Propaganda Policies,” Military Correspondent (PRC), No. 5, 2009. and Ji Chenjie and Liu Wei, “A Brief Discussion of Public Opinion Warfare on the Web,” Military Correspondent (PRC), No. 1, 2009.

[5] Cheng, Cyber Dragon: Inside China’s Information Warfare and Cyber Operations, 52.

[6] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, “Wang Yi elaborates China’s five-point position on the current Ukraine issue.” Retrieved from https://www.mfa.gov.cn/wjbzhd/202202/t20220226_10645790.shtml (accessed April 30, 2022) (In Chinese). “Wang Yi: China proposes a six-point initiative for preventing humanitarian crisis in Ukraine.” Retrieved from https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/web/wjbzhd/202203/t20220307_10648854.shtml (accessed April 30, 2022) (In Chinese).

[7] “Xinhua Commentary: China’s stance on Ukraine serves world fundamental interests.” Xinhua, April 29, 2022. Retrieved from https://english.news.cn/20220429/48fba0f2a5d44475a62fde1ad7d89bb2/c.html (accessed April 30, 2022).

[8] Elizabeth Dwoskin, “China is Russia’s most powerful weapon for information warfare.” The Washington Post, April 8, 2022. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2022/04/08/russia-china-disinformation/ (accessed May 1, 2022).

[9] Vincent Ni, “‘They were fooled by Putin’: Chinese historians speak out against Russian invasion.” The Guardian, February 28, 2022. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/feb/28/they-were-fooled-by-putin-chinese-historians-speak-out-against-russian-invasion (accessed April 30, 2022).

[10] Waiyee Yip, “5 professors from top Chinese universities wrote an open letter condemning Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, marking a departure from China’s pro-Russian online sentiment.” Insider, March 2, 2022. Retrieved from https://www.insider.com/nationalist-china-pro-russian-sentiment-online-anti-war-voices-ukraine-2022-3 (accessed April 30, 2022).

[11] The Carter Center, “Chinese Public Opinion on the War in Ukraine.” US-China Perception Monitor, April 19, 2022. Retrieved from https://uscnpm.org/2022/04/19/chinese-public-opinion-war-in-ukraine/ (accessed April 27, 2022).

Kommentar schreiben